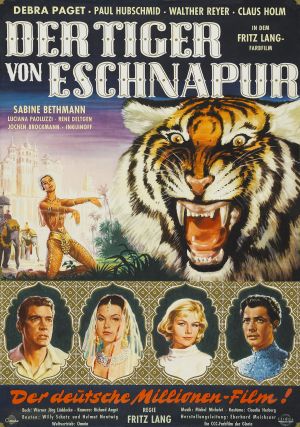

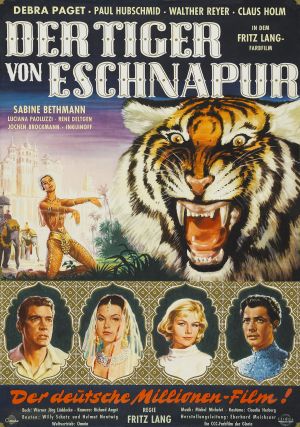

These can perhaps be regarded as typical of German movie poster art of the 1950’s.

It was left to the Italians to show them how to do it right.

By the late 1950’s, Fritz Lang’s Hollywood movie career had come to end. There were no more studio executives left for him to piss off. It was at this time that the German film producer, Artur Brauner, approached Lang and suggested he do a remake of his silent film The Indian Tomb, (which had been completed without Lang’s supervision). Lang agreed, and the resulting work was released as two films: The Tiger of Eschnapu and The Indian Tomb. They were two of the last three films that Lang made before he retired due to failing eyesight.

Lang regarded film as a visual art form rather than as a form of literature, so he had no reservations about using “genre” subject matter: science fiction, detective stories or, in the case of these two films, Orientalist fantasy. In this respect, he is similar to such contemporary directors as George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and James Cameron. Unlike them, however, Lang’s films are never coy or campy. He always treats his subject matter seriously and with respect. For that reason, I consider Lang’s work to be artistically superior to that of these other directors.

From the moment one begins watching The Tiger of Eschnapur, one can see right away that this is an example of what the late Edward Said called “Orientalism”. More than once some character mentions that Europeans can never really understand India. (It doesn’t help that most of the Indian roles are played by Europeans in brown face.) This “Mysterious Orient” nonsense was, of course, used to justify Western imperialism. (The “clash of civilizations” is a more sophisticated, contemporary version of this argument.) This film is based on a 1918 novel written by Lang’s former wife, Thea von Harbou, who wrote the silly story for Metropolis and who later joined the Nazi party (although, interestingly, she secretly married an Indian man). One can, however, enjoy these films on their own terms without worrying about the politics of it. It is simply a remnant from a defunct way of looking at the world.

Harold Barger (Paul Hubschmid) is a German architect who has been hired by Chandra (Walter Reyer), the maharajah of Eschnapur, to design public buildings for his kingdom. On his way to Chandra’s palace, Harold meets Seetha (Debra Paget), a temple dancer with whom the maharajah has fallen in love. The carry out a secret affair, which Chandra eventually discovers. Chandra throws Harold into a pit with a man-eating tiger, but Harold manages to kill it. (The tiger is obviously fake. Don’t worry, no animals were harmed in the making of this film.) Chandra then tells Harold that he has until sunrise to leave Eschnapur. Harold, however, has an assignation with Seetha in a temple, and the two of them flee into the desert. There, they are overcome by the heat and dust. Harold deliriously shoots at the sun just before he collapses. A message then flashes across the screen promising that we can see the miraculous rescue of the lovers in the sequel, which will be “more grandiose” than the first film.

The Indian Tomb is, indeed, more grandiose. Seetha and Harold are rescued by a caravan. Shortly afterwards, however, they are captured by Chandra’s soldiers. True love eventually wins out, though not without a lot of people getting killed in the process.

These are not among Lang’s best films, but they are nonetheless entertaining movies to watch. Lang directed them in a beautiful manner, although he clearly had to deal with a limited budget. Some of the sets and costumes are not quite convincing. And some of the special effects are embarrassing, such as the fakest looking cobra you will ever see. On the other hand, Debra Paget gives not one, but two, erotic dances. Paget, an American, was, like Lang, a refugee from Hollywood. She had refused to abide by the rules of the studio system, so she was blacklisted. She had to go to Europe to find work. I’m told that in her later years Paget became a born-again Christian, and she had her own religiously themed TV show. I wonder if she ever discussed temple dancing on her show.