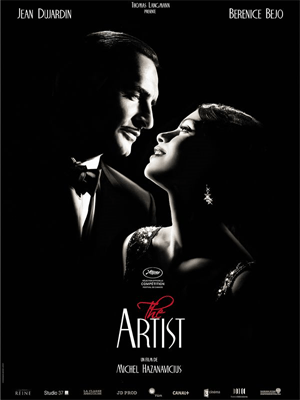

The Artist, written and directed by Michel Hazanavicius, is an homage to the silent film era. There is no recorded dialogue in most of the film. It is described as black-and-white, although it is clear that it was shot in color and then photoshopped into grayscale. (Compare this to any black-and-white film from the 1930’s, and you can see the difference.) Presumably this is because black-and-white film has become prohibitively expensive. It was shot in the 1.33:1 screen ratio that was commonly used up until the advent of television. The period detail is fairly accurate, although in one close-up shot one can see that Dujardin is wearing a synthetic moustache. And in one scene, when two of the characters meet on an upper story staircase in a movie studio (most studio buildings are only one or two stories), there are so many extras rushing back and forth in the background, the place looks almost like an ant colony.

The story is largely lifted from A Star is Born, with a bit of Sunset Boulevard and the Rin Tin Tin movies thrown in. Geroge Valentin (Jean Dujardin) is a silent film star who appears in adventure movies with his dog, Jack. By chance, he meets an extra, Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo), and he is immediately taken with her. He persuades a reluctant producer (John Goodman) to give her a bit part in a movie. Within a few years, Peppy (don’t you hate that name?) becomes a big star. When sound films are introduced, Valentin dismisses them. He uses his own money to finance a silent film. However, it comes out the day after the stock market crashes. What’s more, a sound film starring Peppy premieres the same day, and everybody goes to see that. George loses his shirt, and he drifts into poverty and alcoholism. He sells off most of his belongings at an auction, where they are secretly bought by Peppy, who hasn’t forgotten him. However, George’s loyal manservant, Clifton (James Cromwell) stays with him, even though George can no longer pay him. Clifton reluctantly leaves only after George orders him to. (We’re supposed to believe this?) Depressed, George burns his old films, and his house catches fire. Jack runs to alert a policeman, and George is saved. While George is lying unconscious in a hospital, Peppy arranges to have him moved to her home, where, coincidentally, Clifton now works. When he wakes, George wanders through Peppy’s house, where he finds a room full of his old belongings. Shocked, he returns to his house, where he prepares to shoot himself, while Jack pleads with him not to. Peppy shows up and apologizes. The film ends with Peppy and George dancing in a musical number.

The Artist has some amusing moments. For example, when George learns of the new sound film technology, he has a nightmare is which he hears sounds. For the most part, however, I felt as though I had been here many times before. (Think of those movie spoofs on the old Carol Burnett Show.) Hazanavicius says this movie is meant as a tribute. Yet, by filling it with clichés, he shows a condescending attitude towards the silent films he supposedly adores.