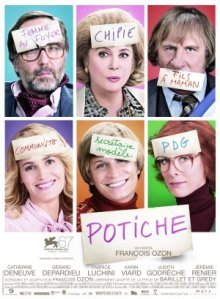

The wikipedia article on François Ozon, says he is “a French film director and screenwriter and [sic] whose films are usually characterized by sharp satirical wit and a freewheeling view on human sexuality.” In Potiche (Trophy Wife), Ozon’s latest film, there is some of the latter and only a little bit of the former.

The time is the 1970’s. Suzanne (Catherine Deneuve) is the stay-at-home wife of Robert (Fabrice Luchini), who runs the umbrella factory that belonged to Suzanne’s father. Robert has affairs with other women, including with his secretary, Nadège (Karin Viard). When the workers at the factory go on strike, Robert assaults one of them. The workers retaliate by taking Robert hostage. Suzanne appeals to Maurice (Gérard Depardieu), a Communist member of Parliament who also happens to be Suzanne’s onetime lover, to intervene. He persuades the workers to release Robert, promising them there will negotiations to address their grievances. After his release, Robert suffers a heart attack. Suzanne, who has never worked before in her life, takes his place. She negotiates a new contract with the workers. She hires her children, Joëlle (Judith Godrèche) and Laurent (Jérémie Renier), to help her run the business. The company begins to prosper. Suzanne finds that she likes being a businesswoman. She begins seeing Maurice. When Robert returns from the hospital, he demands that Suzanne turn the business back over to him. Suzanne refuses, and she tells Robert that he should stay at home from now on. Meanwhile, Maurice becomes indignant when he learns that he was only one of several lovers that Suzanne had when she was young. He helps Robert in a scheme to take control of the business away from Suzanne. She retaliates by running for Maurice’s parliamentary seat.

Suzanne’s transition from trophy wife to businesswoman and then politician is apparently supposed to be seen as personal liberation. Yet her political campaign is inane. Her slogan is “Liberty Lights our Way”, which doesn’t really mean anything. We are never told what her positions are, or even if she has any. We see her visit a dairy farm, where she talks about how wonderful cheese is. In the final scene, she addresses her supporters after she has just won the election. She tells them they are her “children”. She then sings C’est beau la vie. The film ends with an overhead camera shot, with Suzanne looking upwards, surrounded by her supporters gazing adoringly at her. So, is this Ozon’s idea of feminism? The politician as Super Mom? For Ozon’s sake, I would like to believe that he is trying to be ironic here, but the cynical part of me tells me that he isn’t. After all, many liberals admire the vapid, self-promoting Arianna Huffington. What’s more the film gives the idea that there would be no problems with capitalism if we just had “good people” (most likely women) running things. If only the world were that simple.